Clan Murray

| Clan Murray | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Moireach | |||

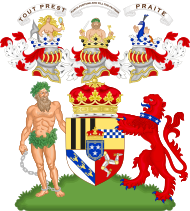

Crest: On a Wreath Or and Sable a demi-savage Proper wreathed about the temples and waist with laurel, his arms extended and holding in the right hand a dagger, in the left a key all Proper. | |||

| Motto | Furth fortune and fill the fetters[1] | ||

| Profile | |||

| Region | Highlands and Lowlands | ||

| Plant badge | Butcher's Broom,[1] or Juniper | ||

| Pipe music | The Atholl Highlanders | ||

| Chief | |||

| |||

| Bruce Murray | |||

| 12th Duke of Atholl | |||

| Seat | Blair Castle[2] | ||

| Historic seat | Bothwell Castle[2] | ||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

Clan Murray (ⓘ) is a Highland Scottish clan.[3] The chief of the Clan Murray holds the title of Duke of Atholl. Their ancestors were the Morays of Bothwell who established the family in Scotland in the 12th century. In the 16th century, descendants of the Morays of Bothwell, the Murrays of Tullibardine, secured the chiefship of the clan and were created Earls of Tullibardine in 1606. The first Earl of Tullibardine married the heiress to the Stewart earldom of Atholl and Atholl therefore became a Murray earldom in 1626. The Murray Earl of Atholl was created Marquess of Atholl in 1676 and in 1703 it became a dukedom. The marquess of Tullibardine title has continued as a subsidiary title, being bestowed on elder sons of the chief until they succeed him as Duke of Atholl.

The Murray chiefs played an important and prominent role in support of William Wallace and Robert the Bruce during the Wars of Scottish Independence in the 13th and 14th centuries. The Murrays also largely supported the Jacobite House of Stuart during the Jacobite risings of the 18th century. Clan Murray hold the unique position of commanding the only private army in Europe known as the Atholl Highlanders.

History[edit]

Origins of the Clan[edit]

The progenitor of the Clan Murray was Freskin who lived during the twelfth century.[3][4] It has been claimed that he was Pictish but it is much more likely that he was a Flemish knight, one of a ruthless group of warlords who were employed by the Norman kings to pacify their new realm after the Norman conquest of England.[3] David I of Scotland who was brought up in the English court, employed such men to keep hold of the wilder parts of his kingdom and granted to Freskin lands in West Lothian.[3] The ancient Pictish kingdom of Moray (Moireabh in Scottish Gaelic) was also given to Freskin and this put an end to the remnants of that old royal house.[3] In a series of astute political moves Freskin and his sons intermarried with the old house of Moray to consolidate their power.[3] Freskin's descendants were designated by the surname de Moravia ("of Moray" in the Norman language) and this became 'Murray' in the Lowland Scottish language.[3] The original Earls of Sutherland (chiefs of Clan Sutherland[note 1]) descend from Freskin's eldest grandson, Hugh de Moravia,[3][5] whereas the chiefs of Clan Murray descend from Freskin's younger grandson, William de Moravia.[5]

Sir Walter Murray became Lord of Bothwell in Clydesdale thanks to a marriage to an heiress of the Clan Oliphant.[3] He was a regent of Scotland in 1255.[3] He also started construction of Bothwell Castle, which became one of the most powerful strongholds in Scotland.[3] It was the seat of the chiefs of Clan Murray until 1360 when it passed over to the Clan Douglas.[3]

Wars of Scottish Independence[edit]

During the Wars of Scottish Independence, Andrew Moray took up the cause of Scottish independence against Edward I of England and he was joined by William Wallace.[3] Andrew Moray was killed following the Scottish victory at the Battle of Stirling Bridge in 1297, after which Wallace assumed command of Scottish forces.[3][6] It has been suggested that the whole war might have taken a different course if Moray had survived the battle at Stirling Bridge as he had shown significant skill in pitched battle, which Wallace lacked.[3] His son was Sir Andrew Murray, 4th Lord of Bothwell and third Regent of Scotland who married Christian Bruce, a sister of king Robert the Bruce.[6] This Andrew Murray fought at the Battle of Halidon Hill in 1333.[3]

The lordship of Bothwell passed to the Douglases in 1360 when the fifth Murray Lord of Bothwell died of plague and his wife, Joan (herself daughter to Maurice de Moravia, Earl of Strathearn), took Archibald the Grim, Lord of Galloway and later Earl of Douglas, as her second husband.[3]

15th- and 16th-century clan conflicts[edit]

The Murray's feuds with their neighbours were not as numerous as those of many other clans.[6] However, one incident of note, the Battle of Knockmary in 1490 pitted Murrays of Auchtertyre against the Clan Drummond.[6] In 1562, at the Battle of Corrichie, Clan Murray supported Mary, Queen of Scots against George Gordon, 4th Earl of Huntly.[7]

There were many branches of the Clan Murray who disputed the right to the chiefship.[3] It was not until the 16th century that the Murrays of Tullibardine are recorded as using the undifferenced arms of Murray in 1542,[8] in a work that pre-dates the establishment of the Lord Lyon's register of 1672 and is considered of equal authority.[3] The claim to the chiefship by the Murrays of Tullibardine rested upon their descent from Sir Malcom, sheriff of Perth in around 1270 and younger brother of the first Lord of Bothwell.[3][4] The Murrays of Tullibardine consolidated their position as chiefs with two bands of association in 1586 and 1598 in which John Murray, later the first Earl of Tullibardine, was recognized as chief by numerous Murray lairds including the Morays of Abercairny in Perthshire who were amongst the signatories.[3]

In the bond of 1586 it is stated, "with the hail name of Murray and others undersubscribing"...."as God forbid, the offendar to be object to (by) the rest, and accounted from thencefurth enemy to them all..." and signed by: Sir John Murray of Tullibardine, Knight, Sir Andrew Murray of Aryngosk, William Moncrieff of that ilk, Robert Murray of Abercairny, Johnne Murray of Tibbermuir, James Murray of Pardens, William Murray of Airlywith, Alexander Murray of Airlywith, Johne Murray of Strowane, James Murray, Fiar of Strowane, David Murray, apparand of Letterbanachie, Patrick Murray of Ochtertyre, William Murray of Pitcairles, Alexander Murray of Drumdeway, Patrik Murray of Raith, William Murray, apparand of Abercairny, Mungow Murray of Fedalis, David Murray of Raith, Andro Murray of Lacok, Humphra Murray of Buchanty, Hew, son to Wm Moncrieff of that ilk, David Murray, Howmichael.[9]

In 1594 the Murrays fought on the side of Archibald Campbell, 7th Earl of Argyll, chief of Clan Campbell at the Battle of Glenlivet against George Gordon, 1st Marquess of Huntly, chief of Clan Gordon.[10]

The bond of 1598 is styled a "Bond of Association of the Name Murray" and is signed by Sir John Murray of Tulibardin, James Murray (younger) of Cockpuill, Blackbarony, Mr William Murray, Parson of Dysart, Androw Moray of Balvaird, Patrick Murray of Falahill, William Murray (younger) of Pomauis, Johne Morray, portioner of Arby, Antone Murray of Raith, Patrick Morray of Lochlan, Alexander Murray of Drumdeway, Colonel, John Murray of Tibbermuir, William Murray, appirand of Tullibardin, William Moray of Ochtertyre, (William) Murray of Abercairnay, Alexander Murray of Woodend, Walter Murray, portioner of Drumdeway, Johne Murray, portioner of Kinkell.[9]

17th century and civil war[edit]

In the early 17th century a deadly feud broke out between the Murrays of Broughton and Clan Hannay which resulted in the Hannays being outlawed.[11]

Sir John Murray of Tullibardine, 1548-1613, who was created first Earl of Tullibardine in 1606, married Catherine Drummond and Elizabeth Haldane. His son William Murray, 2nd Earl of Tullibardine married Dorothea Stewart, heiress to the Earls of Atholl.[3] The Stewart earldom of Atholl became a Murray earldom in 1629 and a marquessate in 1676.[3]

The chief of Clan Murray, James Murray, 2nd Earl of Tullibardine, was initially a strong supporter of King Charles I, receiving the leader of the royalist army, James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose at Blair Castle in 1644, and he raised no fewer than eighteen hundred men to fight for the king.[6][12] It was this addition of men that won Montrose the Battle of Tippermuir in 1644.[6][12]

18th century and Jacobite risings[edit]

In 1703 the Murrays as Earls and Marquesses of Atholl were created Dukes of Atholl, reaching the pinnacle of the peerage.[3]

War in France[edit]

John Murray, Marquis of Tullibardine was killed fighting for the British at the Battle of Malplaquet (1709), a major conflict of the War of the Spanish Succession between France and a British-Dutch-Austrian alliance.[6] In 1745, Lord John Murray's Highlanders fought for the British against the French at the Battle of Fontenoy.[13]

Jacobite rising of 1715[edit]

During the Jacobite rising of 1715 the Atholl men (Clan Murray) consisted of 1400 men who were formed into four regiments that were each commanded by William Murray, Marquess of Tullibardine, Lord Charles Murray (younger son of John Murray, 1st Duke of Atholl), Lord George Murray and William Murray, 2nd Lord Nairne.[14] During the Battle of Sheriffmuir, Tullibardine did duty as Major-General of the whole Jacobite army with his battalion of Athollmen having been put under the temporary command of his cousin, John Lyon, 5th Earl of Strathmore and Kinghorne, whose own regiment had gone to England under Brigadier McIntosh. The battle was indecisive as although the Jacobite army's right wing had defeated the Government's left, the Government army's right wing had also defeated the Jacobite left and so both sides claimed victory.[15]

Jacobite rising of 1719[edit]

At the Battle of Glen Shiel in 1719 men of Clan Murray fought under William Murray, Marquess of Tullibardine against the Government in support of the Jacobite cause. Tullibardine was wounded but escaped to France. The following month the Government put up a proclamation offering £2000 for his apprehension.[16] On 25 July 1745 he landed with the Young Pretender, (Charles Edward Stuart), at Borodale, Scotland to launch the Jacobite rising of 1745. General Wade's report on the Highlands in 1724, estimated the clan strength, of the Athol men, at 2,000.[17]

Jacobite rising of 1745[edit]

The first Duke of Atholl's younger son was Lord George Murray, a Jacobite general who was the architect of the early Jacobite successes of the Jacobite rising of 1745.[3] Most military historians concur that if Lord George Murray had been given the sole command of the Jacobite army that the Old Pretender (James Francis Edward Stuart) might well have gained his throne.[3] Lord George's elder brother, the next duke, supported the British-Hanoverian Government,[3] and George's half-brother, Lord John Murray, was made Colonel of the 43rd Regiment of Foot (later the 42nd), in April, 1745.[18] As a result, at the Battle of Prestonpans in September, 1745, there were Murray regiments on both sides. Lord George Murray would go on to lead the Jacobite charge at the Battle of Falkirk (1746) and the Battle of Culloden (1746).[3] He died in exile in the Netherlands in 1760.[3]

- Aftermath

After Culloden, on 27 April 1746, William Murray, Marquess of Tullibardine, who had landed with the Jacobite leader, Charles Edward Stuart in Scotland, suffering from bad health and fatigue, surrendered to a Mr Buchannan of Drummakill. He was taken to the Tower of London, where he died on 9 July. Lord George Murray escaped to the continent in December 1746, and was received in Rome by the Prince's father, the "Old Pretender" (James Francis Edward Stuart), who granted him a pension. Despite this, when Murray journeyed to Paris the following year, the Prince refused to meet with him. Murray lived in numerous places on the continent over the next years, and died in Medemblik, Holland, on 11 October 1760, at the age of 66. John Murray of Broughton who had been secretary to Prince Charles Edward Stuart earned the enmity of the Jacobites by turning king's evidence.

Atholl Highlanders[edit]

Although the Battle of Culloden was the last time the Highlanders of Atholl went to war, the Murray chief's ceremonial guard which became known as the Atholl Highlanders still has the unique honour of being Europe's only legal private army.[3] In 1845 Queen Victoria presented colours to the Atholl Highlanders.[3]

Castles[edit]

Castles that have been owned by the Clan Murray have included amongst many others:

- Blair Castle is the current seat of the chief of Clan Murray, the Duke of Atholl.[2] The castle is in fact now a large white-washed mansion that incorporates part of an old thirteenth century castle.[2] The Clan Comyn once had a stronghold at Blair Castle and the property was then owned by the Stewart Earls of Atholl, but in 1629 it passed by marriage to the Murrays who became Earls, Marquesses and Dukes of Atholl.[2] During the Scottish Civil War, James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose used Blair Castle as a mustering point before the Battle of Tippermuir.[2] In 1653 the castle was besieged, captured and partially destroyed with gunpowder by the forces of Oliver Cromwell.[2] However, the castle was still complete enough for the Earl of Atholl to try and recapture it in the following year.[2] John Graham, 1st Viscount Dundee (Bonnie Dundee of Claverhouse) garrisoned the castle and his body was brought back there after he was killed at the Battle of Killiecrankie in 1689.[2] During the Jacobite rising of 1745 Charles Edward Stuart (Bonnie Prince Charlie) stayed at the castle.[2] However, the following year the castle was occupied by British-Hanoverian forces and it was then besieged and damaged by Jacobites under Lord George Murray and as such is the last castle in Britain to have been besieged.[2] (See: Siege of Blair Castle). In 1787 the castle was visited by Robert Burns.[2] The castle is also home to the Atholl Highlanders who have their yearly spring gathering there.[2] Although Blair Castle is still the seat of the Duke of Atholl, chief of Clan Murray he now lives in South Africa, but the castle is open to the public.[2]

- Bothwell Castle, a few miles north-west of Hamilton, South Lanarkshire was a property of the Murrays (or Morays) from the middle of the twelfth century and it had passed to them from the Clan Oliphant.[2] During the Wars of Scottish Independence Bothwell Castle changed hands between the English and the Scots on several occasions and held a strategic position.[2] The castle was the headquarters of the English Aymer de Valence, 2nd Earl of Pembroke but was surrendered to the Scots in 1314.[2] The keep was demolished at this time and although it was later made defensible it was never restored to its former glory.[2] The castle was rebuilt by Edward Balliol but in around 1337 it was taken by the Scots and again slighted by Sir Andrew Murray.[2] The last Murray laird of the castle died of plague in about 1360 and the property passed to the Earl of Douglas, then to the Douglas Earls of Angus, then to the Hepburn Earls of Bothwell, then back to the Douglas Earls of Forfar.[2]

- Ormond Castle also known as Avoch Castle, three miles south-west of Fortrose on the Black Isle was formerly in Moray and a property of the Murrays.[2] It was once a strong castle but little remains.[2] Sir Andrew Murray died at Ormond Castle in 1338 and the lands went to the Douglases.[2]

- Tullibardine Castle was about two miles north of Auchterarder, Perthshire and was a large building.[2] The nearby Tullibardine Chapel was founded by Sir David Murray of Tulliebardine in 1446 and has been used as a burial place by the Murrays since the Protestant Reformation.[2] The chapel is now in the care of Historic Scotland and is open to the public.[2] The castle was a property of the Murrays from 1284 and Andrew Murray of Tullibardine supported Edward Balliol, playing an important part in the victory at the Battle of Dupplin Moor, and as a result he was executed for treason in 1332.[2] The Murrays of Tullibardine later fought at the Battle of Flodden in 1513, supported Mary, Queen of Scots and turned against her when she married the Earl of Bothwell.[2] Sir John Murray was made Earl of Tullibardine in 1606 and this title was advanced to Marquess of Tullibardine in 1676.[2] William Murray, Marquess of Tullibardine supported the Jacobite risings of 1715, 1719 and 1745, and he died in captivity in the Tower of London in 1746.[2]

- Huntingtower Castle north-west of Perth is a well-preserved castle that consists of two towers; one from the fifteenth century and one from the sixteenth century.[2] The castle was originally held by the Clan Ruthven and was known as Ruthven Castle, but the property was forfeited and the Ruthven name was proscribed following the Gowrie Conspiracy in 1660.[2] The property then went to William Murray, Earl of Dysart, then to the Murrays of Tullibardine and then to the Murray Marqueses and Dukes of Atholl.[2] Huntingtower Castle was the birthplace of the Jacobite Lord George Murray.[2] It was sold to the Mercers in 1805 but is now in the care of Historic Scotland and is open to the public.[2]

- Balvaird Castle, four miles south of Bridge of Earn, Perthshire is a well preserved L-plan tower house that originally belonged to the Clan Barclay but passed to the Murrays of Tullibardine in 1500,[2] and part of the feudal Lordship and Barony of Balvaird.

- Scone Palace two miles north of Perth dates from 1802 but incorporates older work that possibly dates from 1580.[2] The kings of Scots were inaugurated at Scone.[2] After the Reformation, Scone had gone to the Ruthvens but after the Gowrie Conspiracy mentioned above it was granted to the Murrays as Sir David Murray of Gospertie had been one of those who had saved the king's life during the conspiracy.[2] These Murrays were made Viscounts of Stormont in 1602 and Earls of Mansfield in 1776.[2] In 1716 James Francis Edward Stuart held court at Scone and James Murray, second son of the fifth Viscount supported the Jacobites, escaping to France.[2]

- Comlongon Castle, eight miles south-east of Dumfries was held by the Murrays of Cockpool from 1331.[2] It is a substantial keep and tower that rises five storeys and stands alongside a castellated mansion.[2]

Clan chief[edit]

- Clan chief: Bruce Murray, 12th Duke of Atholl, Marquess of Atholl, Marquess of Tullibardine, Earl of Atholl, Earl of Tullibardine, Earl of Strathtay and Strathardle, Viscount of Balquhidder, Viscount of Glenalmond, Lord Murray of Tullibardine.

Badges and crest[edit]

The current Clan badge, (see above), depicts a demi-savage (the upper half of a wreathed, shirtless man) holding a dagger in his right hand and a key in his left. The Clan motto reads Furth, Fortune, and Fill the Fetters, meaning, roughly, go forth against your enemies, have good fortune, and return with captives. The demi-savage badge was favoured by the late Duke of Atholl; the Clan continues to use it out of respect.

An older badge depicts a mermaid holding a mirror in one hand and a comb in the other, with the motto Tout prêt, Old French for all ready. This badge is found in many historical and heraldic sources, and remains a valid Murray device.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ The chiefs of the Clan Sutherland and Clan Murray shared a common ancestor in the direct male line.[4] The surname of both families was originally "de Moravia" meaning "of Moray" or "of Murray" and as a result there were some people by the name of Murray who were septs of the Clan Sutherland in the far north. Most notably the Murrays or Morays of Aberscross who were the principal vassals of the Earl of Sutherland and were charged with the defense of the shire.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Clan Murray of Atholl Profile[permanent dead link] scotclans.com. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq Coventry, Martin (2008). Castles of the Clans: The Strongholds and Seats of 750 Scottish Families and Clans. Musselburgh: Goblinshead. pp. 444–450. ISBN 978-1-899874-36-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Way, George of Plean; Squire, Romilly of Rubislaw (1994). Collins Scottish Clan & Family Encyclopedia. Glasgow: HarperCollins (for the Standing Council of Scottish Chiefs). pp. 284–285. ISBN 0-00-470547-5.

- ^ a b c Atholl, John James Hugh Henry Stewart-Murray (1908). Chronicles of the Atholl and Tullibardine Families. Vol. I. Edinburgh: Privately printed at the Ballantyne Press. pp. 1-3. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ a b Sutherland, Malcolm (1996). A Fighting Clan, Sutherland Officers: 1250 – 1850. Avon Books. p. 3. ISBN 1-897960-47-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g Clan Murray History. electricscotland.com. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ^ Mackay, Robert (1829). History of the House and Clan of the Name MacKay. 233 High Street, Edinburgh: Printed for the author, by Andrew Jack & Co. pp. 131–133.

Quoting: 'Scots Acts of Parliament'

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Lindsay, Sir David (1490-1555); Laing, David (1793-1878) (1878) [Published from original manuscript of 1542]. Fac simile of an ancient heraldic manuscript : emblazoned by Sir David Lyndsay of the Mount. Lyon king of armes 1542. Edinburgh: W. Paterson. p. 109. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

Murray of Tulybairne

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Atholl, John James Hugh Henry Stewart-Murray (1908). Chronicles of the Atholl and Tullibardine Families. Vol. I. Edinburgh: Privately printed at the Ballantyne Press. pp. 17-21. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ Mackinnon, Charles (1995). Scottish Highlanders. Barnes & Noble. ISBN 978-0880299503.

- ^ Way, George and Squire, Romily (1994). pp. 162-163.

- ^ a b Atholl, John James Hugh Henry Stewart-Murray (1908). Chronicles of the Atholl and Tullibardine Families. Vol. I. Edinburgh: Privately printed at the Ballantyne Press. pp. 119-120. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ Loudon's Highlanders History. electricscotland.com. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- ^ Atholl, John James Hugh Henry Stewart-Murray (1908). Chronicles of the Atholl and Tullibardine Families. Vol. II. Edinburgh: Privately printed at the Ballantyne Press. pp. 194-195. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ Atholl, John James Hugh Henry Stewart-Murray (1908). Chronicles of the Atholl and Tullibardine Families. Vol. II. Edinburgh: Privately printed at the Ballantyne Press. p. 202. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ Atholl, John James Hugh Henry Stewart-Murray (1908). Chronicles of the Atholl and Tullibardine Families. Vol. II. Edinburgh: Privately printed at the Ballantyne Press. p. 290. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ Johnston, Thomas Brumby; Robertson, James Alexander; Dickson, William Kirk (1899). "General Wade's Report". Historical Geography of the Clans of Scotland. Edinburgh and London: W. & A.K. Johnston. p. 26. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ Atholl, John James Hugh Henry Stewart-Murray (1908). Chronicles of the Atholl and Tullibardine Families. Vol. II. Edinburgh: Privately printed at the Ballantyne Press. p. 476. Retrieved 3 October 2020.